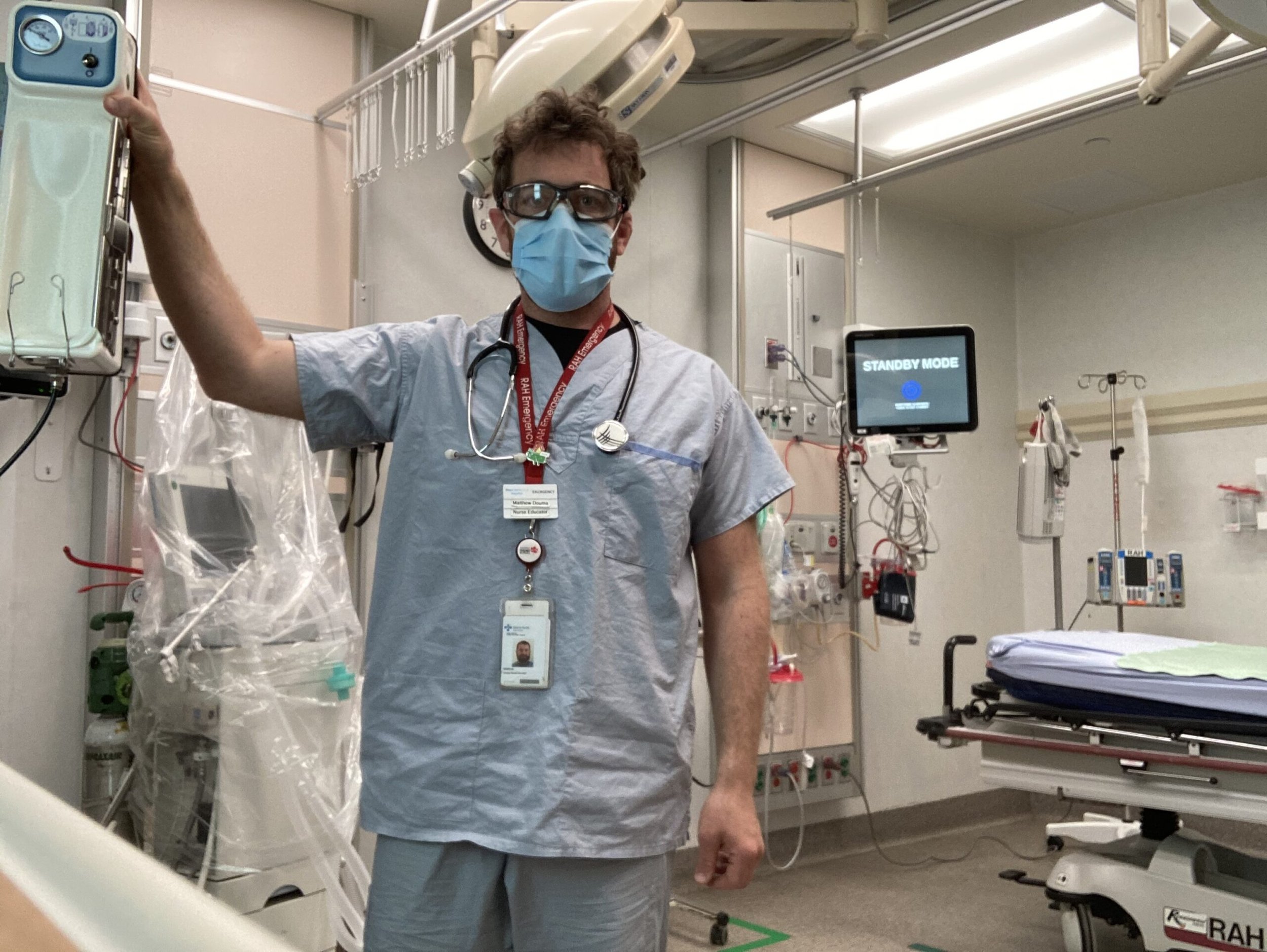

Matthew Douma, RN - How Nurses Impact Patient Outcomes

How Nurses Impact Patient Outcomes

An interview with Matthew Douma, RN

Imagine the fate of a loved one rested in the hands of someone who couldn’t afford to complete their specialized training on a new life-saving technique. Now imagine it was in the hands of someone who could.

Matthew Douma is a nurse, researcher, educator and father of three who has dedicated his career to improving patient outcomes through informed research and knowledge-sharing. While he may not be able to leap tall buildings in a single bound, the leaps he’s made in advancing medical care are the stuff of hero work. In the world of medicine, knowledge is everything and Matt is on a mission to put as much of it as possible into the hands of every healthcare worker.

1. What drew you to nursing?

At first, it was the employability and job opportunities that attracted me. We can work in hospitals, outposts, cruise ships, research and education. What’s kept me in nursing has been the ability to work clinically, teach and contribute through innovation and research.

2. As a nurse, researcher, educator and father of three small children, you must often feel the effects of pressure and exhaustion. What keeps you going?

The pandemic is exhausting…so emotionally exhausting. At the same time, the opioid crisis and increasing methamphetamine use in the inner city has been a particularly acute challenge.

It’s hard to know what keeps us all going. At this point, it might be the old-fashioned clichés of duty and service. It’s important to me that when people need care – when they are at their most vulnerable – that there are expert, life-saving and compassionate nurses there for them. I keep coming back because I want to maintain the care of the most vulnerable persons in our community.

3. How has the assistance you’ve received through ARNET impacted you on a personal level?

ARNET support makes my research and innovation possible. Without the support of ARNET, my work would not be possible. It’s facilitated buying equipment that helps us understand why women are less likely to receive CPR by the public; it’s helped us research what the care needs are of families experiencing sudden cardiac arrest; and they help me fund the statistical and analytical support I need to perform these studies.

4. How has the specialized knowledge you’ve attained through your ongoing learning translated in the quality of care you provide?

In my role as a clinician scientist, any questions that come directly from patient care can inform our research questions and improve patient care. An example of an intervention we’ve studied and improved is the use of proximal external aortic compression, which is a hemorrhage control technique that’s gone on to save the lives of multiple people who otherwise would not have survived. Our work around the improvement of cardiac arrest recognition has resulted in numerous healthcare professionals sharing their experience of recognizing seizure and gasping as cardinal symptoms of cardiac arrest.

5. You have post-graduate specialty training in critical care, a master’s degree in nursing and are currently engaged in resuscitation research that could prove invaluable for those treating patients with COVID-19. What are your future plans for learning?

I’m in the middle of a PhD which is focused on developing family-centered cardiac arrest care principles with a group of people who have lived experience. They’re either survivors themselves, or family members of those who either survived or did not. We’re also working on improving the cardiac arrest care of COVID-19 patients by understanding and improving prone resuscitation.

6. What do we currently misunderstand about the nursing profession and/or medical care that you wish more people knew about?

That nurses (especially in-hospital) are the closest to patients and have a difficult-to-measure and difficult-to-explain role. They are absolutely essential to the provision of safe and high-quality care. We catch and prevent errors, make sure the right people, supplies, equipment and processes are in place to get the best patient outcomes. And since we spend the most amount of time alongside patients, we’re often in the privileged position of knowing things like patient preferences and values.

7. You once assisted a man with a gunshot wound by using a life-saving technique you’d learned through training with UNICEF. Unbeknownst to you, the paramedics who took him into care after you were unaware of the same compression technique. Can you share how that event affected you and may have shifted your view of the medical profession?

It certainly is not the paramedics’ fault. This was an example of a knowledge translation gap. The knowledge of the life-saving technique was in textbooks for post-partum hemorrhage, but they had not been translated for use in trauma care.

This is when I began my research and innovation work. We wrote about this case, designed research studies about its use and then began advocating for this evidence-based intervention, once we had created the evidence. This was when I realized I could help improve the lives of the most patients possible through research and innovation.